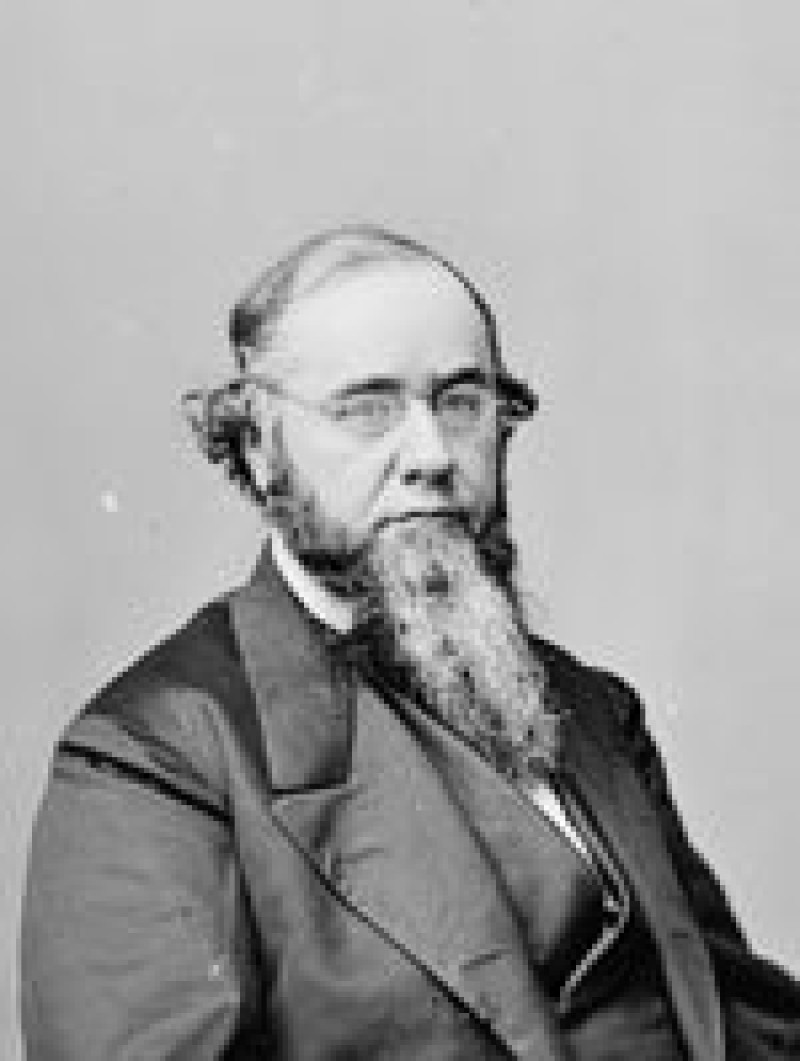

Edwin McMasters Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton, U.S. attorney general and secretary of war, was born in Steubenville, Ohio. Stanton attended local academies and, after his father's death in 1827, took a position as an apprentice in a Steubenville bookstore. In 1831 he entered Kenyon College, but his family's financial problems forced him to leave the following year. After working briefly at a bookstore in Columbus, Stanton returned to Steubenville to study law in the office of his guardian, Daniel L. Collier.

In 1837 Stanton was elected prosecuting attorney of Harrison County, and during the following year he promoted Tappan's successful campaign for the U.S. Senate. From 1842 to 1845 he served as recorder of the Supreme Court of Ohio in Columbus. Since his Kenyon stay, Stanton had harbored strong moral objections to slavery. He chose to keep his antislavery beliefs separate from his political stand, however.

In 1847 Stanton moved to Pittsburgh in search of more lucrative opportunities and, in partnership with Charles Shaler, soon developed an extensive law practice in both Pennsylvania and Ohio. A tireless worker who relied on extensive case preparation, Stanton possessed a keenly logical mind and a forceful speaking style. He was also aggressive, even ruthless, in the courtroom, given to browbeating witnesses and treating with rude contempt opposing lawyers whom he considered his social or intellectual inferiors.

In 1856 Stanton moved to Washington, D.C., in hopes of developing his practice before the Supreme Court. Although he remained ostensibly aloof from politics, he formed a close friendship with Jeremiah S. Black, James Buchanan's attorney general, whom he had known when Black was chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

After Abraham Lincoln's inauguration in March 1861, Stanton remained in Washington, D.C., serving occasionally as a legal consultant to Secretary of War Simon Cameron. He also formed a close friendship with Major General George B. McClellan, the commander of the Department of the Potomac who became commanding general of the army in November. On the issue of slavery, however, Stanton quietly began to separate himself from the conservative Democrats.

On Jan. 13, 1862 Cameron resigned as secretary of war, mainly because of exposes of mismanagement and corruption in the issuing of War Department contracts, and the following day the president appointed Stanton to take his place. Although Lincoln's motives are not entirely clear, the selection seems to have resulted from the influence of Secretary of State Seward, who considered Stanton a moderate.

In July 1862 Lincoln appointed Major General Henry W. Halleck to be commanding general of the army. However, Halleck was reluctant to take full responsibility for directing the military effort, an inclination reinforced by the ill-defined powers of his office, and Lincoln and Stanton continued to shoulder much of the burden. Throughout the middle stages of the conflict, the secretary of war played a central role in appointing and removing commanders, overseeing military operations, and even shaping strategy.

In the Enrollment Act of March 1863, Congress established a militarized provost marshal general's bureau under Stanton's control — in effect a national police force — and the secretary employed this apparatus vigorously to enforce the draft and combat dissent. By mid-war Stanton had transferred his loyalties fully to the Republican party, and he used his official powers to promote the Republican political cause, which he identified with preservation of the Union.

Stanton remained in the War Department after the war and oversaw the demobilization of the Union armies. Initially he supported Andrew Johnson's policies toward the South, even reversing his position to back the president's opposition to the immediate enfranchisement of the freedmen. During the summer of 1865, however, reports of violence against blacks and resistance to military rule in the southern states caused Stanton to shift toward the use of stronger measures.

Stanton was one of the central political figures of the Civil War era and one of the most controversial. He generated intense hostility, in part because of his abrasive personality and autocratic leadership style but more because his position as director of internal security inevitably made him a lightning rod for dissent.