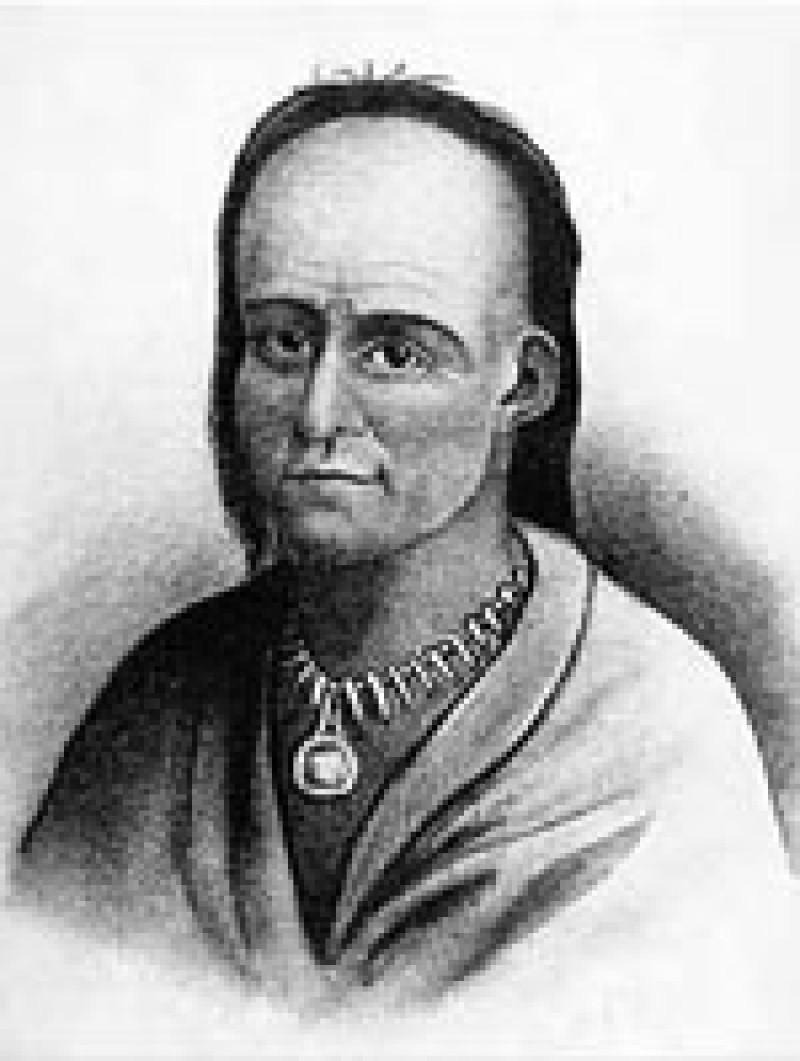

Little Turtle (1752 - July 1812)

Little Turtle, military leader of the Miami Indians of the late 18th century, was born on the Eel River some 20 miles northeast of Fort Wayne, Indiana. A lover of good companionship, fine food and good humor, Little Turtle was a powerful orator who counseled moderation at all times. Six feet in height, he was noteworthy for his subtlety and circumspectness. Little Turtle became one of the most successful woodland military commanders of his time, but after the Treaty of Greenville (1795) he tried to keep his tribe at peace and at the same time protect its land from an imperialist United States.

During the American Revolution, the Miami gave some assistance to the British, and Little Turtle may have participated in the defeat of a detachment led by Augustin de La Balme on its way to attack the British post of Detroit in 1780. After the Peace of Paris (1783) the American Indians continued to resist American expansion north of the Ohio, and Little Turtle probably led small forays against the white settlements. By 1790 he had become the chief military leader of the Miami, serving under a civil chief, Le Gris.

Before 1790 the Miami villages at the head of the Maumee (near present-day Fort Wayne) had become the focus for many American Indians displaced by fighting with the Kentuckians farther east, particularly Shawnees and Delawares. When Brigadier General Josiah Harmar led almost 1,500 troops to attack this concentration in October 1790, burning the American Indian villages, Little Turtle was one of the chiefs orchestrating the defense. The following year an American army general, Arthur St. Clair, advanced upon the Miami towns, but his troops were overwhelmingly defeated in November 1791 by a multitribal force. Miami accounts credit Little Turtle with being the overall American Indian commander on this occasion, although a number of other sources name Blue Jacket.

While Little Turtle's influence was at its apogee, the triumph was overshadowed by General James Wilkinson's unexpected 1791 expedition, which not only destroyed Little Turtle's village on the Eel River but also captured his daughter. When he signed the treaty of Greenville, ending the war, he reputedly said that he was one of the last to sign and that he would be the last to break the treaty.

Little Turtle strongly urged abstinence from alcohol on his fellow Miami and made efforts to have them learn the principles of farming. On one of several trips to the East Coast, he visited Quakers in Pennsylvania in a successful attempt to get farming instructors. This accommodating attitude led him to sign three other major land-losing treaties with the United States. The resultant land cessions made many Miami suspect his integrity; his nephew Richardville died a very rich man. Moreover, some of his critics were right in stating that the Americans wanted nearly all of the American Indian land. Little Turtle's tribal strategy was also doomed by the reluctance of the Miami to alter their older lifestyle. On the other hand, the marked displeasure of Little Turtle and William Wells, Little Turtle's son-in-law (a white captive), at American land hunger also caused American officials, such as William Henry Harrison, governor of Indian Territory, and the Indian agent John Jonston, to distrust him. Nevertheless, Little Turtle's counsels kept the majority of Miami from actively joining Tecumseh's anti-American confederation. In addition, Kentucky relatives of Wells fought prominently in the Battle of Tippecanoe (1811), which severely checked Tecumseh's progress. Little Turtle's reputation began to recover after this military defeat of the hostile confederation, and it was with good reason that the American government buried Little Turtle with full military honors.

The clash of personalities, tribal policies, and pan-tribal strategies that Little Turtle and the Shawnee leaders Blue Jacket and Tecumseh personified in their generation continued to be reflected in 20th century tribal discussions and in the general history of the American Indian.